From climate crisis to crisis of coexistence with living beings: How to resolve the conflict between man and nature?

Yaël Bitter Français | عربي

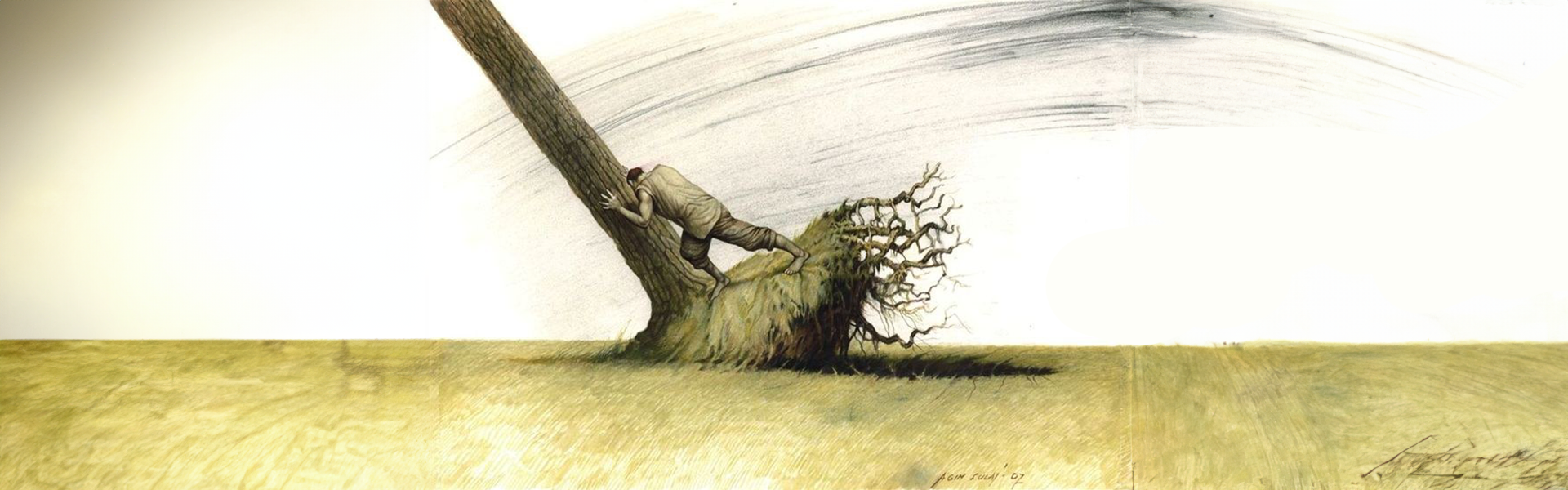

Image: L’uomo E La Natura © Agim Sulaj

“Climate change”, “biodiversity loss”, “increased risk of tension” and “conflict” are commonly used terms, but the explanations given for the links between these phenomena are not conclusive. A growing number of researchers are analysing the links between climate, increased risk of conflict, and peace, and highlighting important facts, such as the fact that when tensions arise, climate tends to be a factor rather than a cause of conflict. Although relevant, these analyses are based on a dualistic model between man and nature and focus on conflicts over the sharing of resources: climate change creates ecological stress, which alters access to resources and in some cases leads to conflict.

Another way of looking at the problem is to take a more global, systemic approach, observing the imbalance between human actions and nature’s responses. When resources are overexploited, it is not just biodiversity that suffers, but a whole complex system that becomes unbalanced. The problem of bee extinction illustrates the vital interdependence between human and non-human actions: humans need these pollinators to survive, and bees need humans not to destroy their habitat so that they can continue to live. So, it’s no longer a question of analysing the impact of human actions on nature, but of understanding the system in which this nature, this creature, lives, not in order to protect it or to dominate it by exploiting it, but to translate it into human language so that we can dialogue and live together.

A third approach considers human-nature conflicts in terms of translation and communication. The terms “human” and “nature” are replaced by “living human” and “living non-human”. Instead of conceiving of vertical relations between man and nature, with man at the top and the rest of the living beings at the bottom, this third approach allows us to reformulate certain concepts in order to conceive of horizontal relations between the living beings on this planet and, as Michael Cronin proposes, “to rethink our identity in terms of horizontal relations with the beings that coexist with us” (Le Temps, 22 March 2023). We are talking about non-human beings, coinhabitants of our planet, who are rising up and demanding that we negotiate the common causes of the crisis we are experiencing, and that we forge vital alliances and communicate in order to work out the practical conditions for optimal coexistence.

We need a “diplomatic cohabitation”, which Baptiste Morizot defines as “a kind of narrative, a convenient fiction, to tell us what kind of relationship to imagine with beings that are no longer just resources or things, and that are indistinguishably intertwined with us without losing their otherness”. (Nouvelles alliances avec la terre. Tracés, 33, 2017). Diplomacy, or diploma in ancient Greek, means “folded in two”. The diplomat can be seen as the person who stands at the interface between two heterogeneous parties, enabling communication “from world to world, from way of being to way of being”, to use Morizot’s words. This person must know a common language, different modes and codes of communication or, if they do not exist, create them. They can be seen as translators, diplomats or mediators. Their role is to establish a dialogue between two parties that cannot coexist. Ultimately, this person translates two visions of the world and provides the tools to transform and resolve a conflict.

Are we experiencing an environmental and societal crisis? Or are we experiencing a crisis in our relationship with non-human beings? If we approach the problem through the second paradigm, i.e. a crisis in our relationship with non-human beings, the conflict transformation approach becomes central. A conflict can be defined as a real or perceived contradiction between the goals of individuals or groups, whether in terms of interests or values. If left unaddressed, conflicts can degenerate into violence. It would therefore make sense to extend this definition to conflicts between living humans and living non-humans. In this context we can think of internal mediation, where the human would be an internal mediator in the conflict. He would then have to wear two hats, having a duty to take sides and then to be impartial in his role as mediator.

Is such a role, such a commitment, conceivable in the conflict between living humans and living non-humans? How would this commitment take shape in practice? These are the kinds of questions that need to be answered if we are to prevent this conflict from degenerating into uncontrollable violence and becoming an existential threat to all parties.

Yaël Bitter

May 2024

Read the full paper | PDF