Religious and Communal Dynamics of Islam in Ivory Coast and Benin

Enver Jusufovic, January 2026 | Français

Introduction

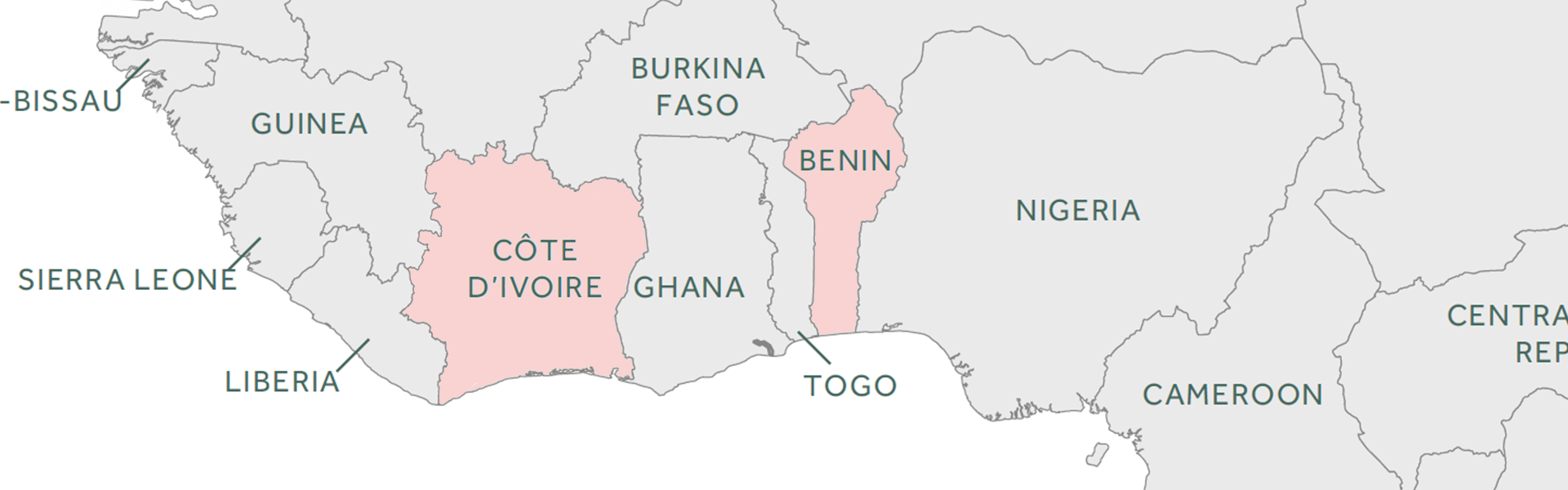

Ivory Coast and Benin, long portrayed as pillars of stability in West Africa, now find themselves at the intersection of increasingly complex religious, social, and security dynamics. Their plural religious landscape—marked by the coexistence of Islam, Christianity, and traditional religions—is the result of several centuries of history, cross-border movements, and regional interactions. This diversity, long considered a source of stability, is now being tested by the expansion of security threats and a range of internal factors.

The geographic position of these two coastal states directly exposes them to the spillover of the Sahelian conflict. Violence affecting Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso—now an epicenter of regional insecurity—is steadily spreading southward. The continued expansion of Jama’at Nasr al-Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM) and other armed groups is gradually transforming the northern borders of Ivory Coast and Benin into areas of increasing vulnerability, posing a direct threat to the entire West African coastline. In Benin, the human cost of violence in 2025 amounted to 179 attacks and 348 deaths[1].

In addition to these external risks, internal factors—such as perceptions of marginalization, gaps in the education system, and certain religious dynamics—are likely to undermine social cohesion and fuel latent tensions. Furthermore, the complexity of the institutional response to the expansion of insecurity acts as an additional driver of political instability, as illustrated by the attempted coup that occurred in Benin on 7 December 2025.

Cordoba Peace Institute (CPI) conducted an exploratory mission in Ivory Coast (Abidjan, Korhogo) and Benin (Cotonou, Parakou) from 9 to 23 June 2025 as part of the Fiqhi Pathways program, which aims to promote violence reduction and dialogue with religiously motivated armed groups in the Sahel region, around Lake Chad, in East Africa, and in Afghanistan. This contribution seeks to provide a contextual analysis of the religious and communal dynamics of Islam in Ivory Coast and in Benin.

Context

Ivory Coast is characterized by strong religious diversity, with approximately 43% Muslims, 40% Christians, and a significant share of traditional religious practices[2]. Islam has been present since the 11th century, introduced through merchant networks from the Sahel. Historically shaped by Sufi orders, the Ivorian Islamic landscape has undergone a gradual transformation from the 1940s onward—and more markedly since the 1980s—with the rise of Salafism. This movement has expanded through preaching, overseas religious studies, and the establishment of mosques and Arabic schools, notably driven by influential figures such as Sheikh El Hadj Mory Moussa and Mohamed Idriss. Today, the movement continues to strengthen through new institutions, including Al-Furqan University.

In the absence of a centralized Islamic authority, part of the Muslim elite founded the Higher Council of Imams, Mosques, and Islamic Affairs (COSIM) in the early 1990s. This organization rapidly became the moral and representative body of the Muslim community, playing a role comparable to that of the Catholic Church in its relations with public authorities. However, COSIM itself is marked by internal tensions between the dominant Sufi orders and Salafist groups, which claim greater institutional representation. These rivalries relate to religious practices, doctrinal legitimacy, and control over places of worship.

Relations between Muslims and Christians are shaped by a complex historical legacy. Christianity became firmly established during French colonization, which granted it a privileged position within the administration[3]. After independence, this influence persisted, and Christianity—particularly Catholicism—retained strong visibility in the political sphere[4]. In the 1990s and 2000s, the politico-identity crisis known as “Ivoirité”, a doctrine defining national identity and citizenship, exacerbated divisions between the predominantly Muslim north and the predominantly Christian south. Violence targeting imams, mosques, and Dioula populations left a lasting mark on collective memory and fueled a sense of injustice within Muslim communities.

The accession to power of Alassane Ouattara in 2011 marked the beginning of an attempt to rebalance state structures in favor of the north, his main electoral base. Several territorial reforms, administrative appointments, and investments strengthened the presence of officials originating from the north within state institutions. While these measures were perceived by some Muslims as long-overdue recognition, they simultaneously fueled among certain Christian groups the perception of “northern domination.”[5]

Thus, despite institutional efforts and a historical record of peaceful coexistence, Ivorian Islam remains marked by internal rivalries, and relations between Muslims and Christians continue to be shaped by sensitive political memories. Social cohesion rests on unstable balances forged by history, contemporary religious dynamics, and national political realignments.

In Benin, Islam was introduced between the 14th and 17th centuries by Songhai traders from the territories of the former Mali Empire. Today, the country presents a plural society composed primarily of Christians (48%), followed by Muslims (28%) and adherents of traditional religions[6].

The Beninese Muslim community is shaped by the same doctrinal dynamics observed in Ivory Coast, particularly the opposition between Sufi and Salafist doctrinal orientations. The most pronounced tensions concern religious legitimacy, interpretation of texts, and institutional representation, even though both religious groups are officially united within the Islamic Union of Benin (UIB), the body intended to federate them.

Relations between Muslim and Christian communities in Benin are also influenced by the legacy of French colonization, which favored Christian institutions.[7] Colonization profoundly structured the distribution of power by privileging southern elites at the expense of the predominantly Muslim northern regions. This north–south divide, inherited from a colonial administration that supported coastal Christianized or animist kingdoms, persisted after independence, with successive southern-dominated governments reinforcing among northern Muslims a lasting sense of marginalization.

To promote national cohesion, Benin established institutionalized platforms for interreligious dialogue, such as the Framework for Consultation among Religious Faiths (Cadre de Concertation des Confessions Religieuses), which brings together Catholic, Protestant, Muslim, and Vodun leaders to address national issues. This mechanism is often presented as a model of religious coexistence; Swiss delegations have studied its functioning, highlighting its role in the stability of political transitions since 1990 and in the organization of symposiums involving state authorities, religious leaders, and traditional representatives.[8] These initiatives have contributed to preventing violence and supporting development, with local officials crediting interreligious dialogue for promoting mutual understanding.

However, despite its effectiveness in fostering national cohesion, this dialogue faces limitations in the face of armed threats—both endogenous and exogenous—in the northern part of the country, where the violence of armed groups and specific instances of state misconduct exceed traditional peace mechanisms.[9] Moreover, although the general situation remains stable, some Muslims continue to perceive a form of marginalization, particularly regarding access to public resources or political responsibility, a sentiment that tends to intensify as major electoral deadlines scheduled for 2026 approach.

Rise of Insecurity in the Northern Regions

Violence today constitutes the principal challenge facing West Africa. The deterioration of the situation in the central Sahel has led to the spread of armed group threats toward the northern regions of coastal states, notably Ivory Coast and Benin.

Since 2013, northern Ivory Coast has faced a growing threat from armed groups linked to Mali and Burkina Faso. This trend escalated from 2015 onward with the expansion of Ansar Dine and JNIM from central and southern Mali. The first major attack on national soil occurred in Grand-Bassam in 2016, resulting in 19 deaths. Since 2020, the country’s northeastern region, particularly the Kafolo area in the Tchologo region, has been regularly targeted by jihadist attacks, causing military fatalities and multiplying incidents involving improvised explosive devices (IEDs). Armed groups have also established bases in border forests and villages, such as Niangoloko in Burkina Faso, strengthening their capacity to conduct cross-border operations and control strategic rural areas.

The political crisis from 2002 to 2011, which deeply divided Ivory Coast, continues to influence its security policy. From 2011 onward, President Alassane Ouattara implemented a strategy combining security reinforcement with structural economic reforms, based on the assumption that growth and its social spillovers would help stabilize the country and restore governmental legitimacy. Compared with Sahelian countries regularly confronted by armed groups, Ivory Coast adopted an integrated approach: strengthening the army, establishing military bases along northern borders, and deploying socio-economic programs in the six most vulnerable regions, offering vocational training and credit facilities to youth and women.

Despite these measures, the country remains vulnerable. Long and porous northern borders, cross-border tracks, informal trade, and illegal gold mining facilitate the infiltration of armed groups. In addition, perceived inequalities in the distribution of economic benefits weaken community resilience. The country’s strategic position and privileged ties with Western partners also expose it to destabilization attempts. Thus, despite notable progress, Ivory Coast continues to face a high level of security risk.

Northern Benin has faced a growing threat since 2019 linked to the presence and movement of armed groups, primarily JNIM. The first significant manifestation of this threat dates back to 1 May 2019, when two French tourists were kidnapped in Pendjari National Park, near the border with Burkina Faso, and their Beninese guide was killed.[10]

The situation worsened from late 2021, with the attack in Porga on 2 December, shortly after the capture of Nadiagou in Burkina Faso, followed by several incidents involving IEDs. These attacks, attributed to JNIM, are explained by the existence of sanctuaries in eastern Burkina Faso and, to a lesser extent, in Niger’s W National Park, facilitating the movement of armed groups within Benin’s W and Pendjari parks. Three distinct JNIM units have been identified along the border with Burkina Faso, with a more limited presence of the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) in the Singou Reserve and W Park. At the same time, JNIM has progressively recruited among local populations, preaching the implementation of Sharia and promising improved access to resources, thereby consolidating its influence[11].

From 2022 onward, the situation shifted from a classic Sahelian spillover to a more complex context involving jihadist groups, Nigerian bandits, and transnational networks. The rise in armed flows, banditry, and links with Nigeria have transformed northern Benin into an operational corridor linking the Sahel and the Lake Chad Basin. Sensitive areas expanded to Alibori, Atacora, Borgou, and the Trois Rivières forest, with incidents including kidnappings, extortion, forced displacement of farmers, and threats against civilians.

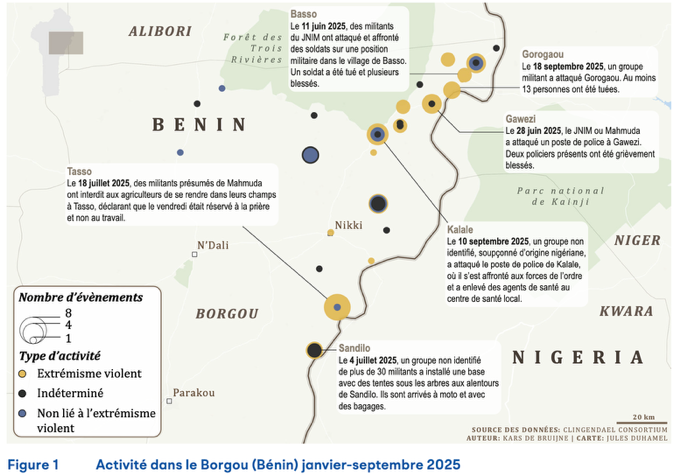

Between 2024 and 2025, JNIM and its hybrid cells—resulting from the merger with dissidents from Boko Haram—intensified their presence, claiming several attacks in Basso and Wara.[12] The January 2025 attack in W National Park was among the deadliest for the Beninese army, with 28 soldiers killed, followed in April by another attack causing 54 deaths. As illustrated in Figure 1,

Nigerian extremist groups have also established themselves in Borgou, near major towns such as Nikki and Parakou, reproducing their governance methods and extending their authority over local populations.

The presence of at least three movements—JNIM, ISGS, and residual Boko Haram networks—in northern Benin creates a highly unstable security environment. Although these groups are rivals and do not form a unified front, they share the same territory, increasing risks for populations and security forces. Violence in Benin is therefore not a simple spillover of Boko Haram: some experts believe it reflects a deliberate JNIM strategy to extend its influence toward the Gulf of Guinea, with the absorption of Nigerian fighters serving as a step toward consolidating its operational capabilities. This situation places Benin before a major challenge: its northern border has become a space of circulation, recruitment, and recomposition of armed groups.[14]

The failed coup attempt of 7 December 2025 in Cotonou demonstrates that the Gulf of Guinea has now become a strategic frontline, and that control over ports and coastlines could condition security in the country’s landlocked regions.[15] The current threat is leading Benin to intensify its military presence and develop an integrated security strategy combining military action, cross-border cooperation, and the strengthening of ties with local communities.

Conclusion

The continued advance of armed groups in northern Benin and toward Ivory Coast reveals that the security threat spilling over from the Sahel into coastal zones now constitutes a structural and enduring risk. The strict military and economic responses deployed so far have shown their limits: not only do groups such as JNIM retain a remarkable capacity for adaptation, but the state, weakened by internal and external pressure, struggles to ensure effective territorial control, particularly along northern borders now transformed into frontier zones. In the face of the gradual erosion of public authority, an alternative approach combining security and socio-political action has become indispensable. This entails strengthening community-centered strategies and broadly disseminating alternative narratives to religiously framed violence.

In this context, the involvement of religious actors appears as a credible pathway, already tested in the past, notably in Ivory Coast where imams played a decisive role in mediation during the Ivoirité crisis and in intercommunal pacification processes. Their engagement helped prevent the violent instrumentalization of religious identities. They leveraged their moral authority to counter political manipulation and promote a genuine culture of social cohesion. Imams occupy a central place within the Muslim community: beyond their spiritual role, they also assume social and political functions, guided by strong patriotism and a nuanced understanding of local realities. They intervene in major societal debates as moderate mediators, embodying an Islam adapted to the multi-confessional West African context.

Within this perspective, Cordoba Peace Institute – Geneva (CPI) is fully embedded in this landscape. Drawing on its recognized expertise in violence prevention, inter and intra faith collaboration, and the promotion of alternative narratives, CPI is well positioned to propose an innovative approach combining the strengthening of social cohesion, mobilization of religious leaders, and local conflict-resolution mechanisms in a context characterized by religious and legal pluralism. Such an approach would complement military efforts while consolidating the social resilience of border communities—a prerequisite for durably curbing the entrenchment of violence.

[1] https://acleddata.com/platform/explorer

[2] Institut National de la Statistique (INS), Recensement Général de la Population et de l’Habitat (RGPH) 2021 : Résultats globaux définitifs, Abidjan, Ministère du Plan et du Développement, 2022.

[3] Kamagate. A, Conseil National Islamique : histoire d’une symphonie inachevée : Eveil de la communauté musulmane de Côte d’Ivoire, Abidjan, Edition Al-Qalam, 2018.

[4] Mayrargue. C, Les dynamiques paradoxales du pentecôtisme en Afrique subsaharienne, IFRI, 2008, p.16.

[5] Entretiens de Crisis Group, représentants du gouvernement, officiers militaires et habitants, Kong, Ferkessédougou, Boundiali et Tengréla, mars 2023.

[6] Institut National de la Statistique et de l’Analyse Économique (INSAE), Quatrième Recensement Général de la Population et de l’Habitation (RGPH-4) de 2013 : Résultats définitifs, Cotonou, République du Bénin, 2016 (disponible en ligne : https://instad.bj/images/docs/insae-statistiques/enquetes-recensements/RGPH/1.RGPH_4/TOME%203.pdf).

[7] Ibid.

[8] Müller Walter, Le Bénin exemple de cohabitation entre religions, Cath.ch, 5 février 2025, https://www.cath.ch/newsf/benin-exemple-de-cohabitation-entre-religions/

[9] Quidelleur, Le Bénin face à la menace djihadiste, IRSEM n°150, Paris, ministère des Armées, novembre 2025, p. 12-15.

[10] Bénin : attaque d’un poste de police à Kérémou, RFI, 9 février 2020.

[11] K. de Bruijne, Laws of Attraction: Northern Benin and Risk of Violent Extremist Spillover, Clingendael, juin 2021.

[12] Kars de Bruijne et Clara Gehrling, Dangerous Liaisons. Exploring the risk of violent extremism along the border between Northern Benin and Nigeria, Clingendael Report, Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael’, La Haye, juin 2024

[13] Kars de Bruijne, Activity in Borgou (Benin), January–September 2025, Clingendael Consortium, cartography by Jules Buramel, 2025.

[14] International Crisis Group, « Le Sahel : une contagion jihadiste vers le sud ? », Rapport Afrique n° 299, Bruxelles, 2023, https://www.crisisgroup.org/fr/africa/sahel/mali/299-le-sahel-une-contagion-jihadiste-vers-le-sud

[15] Bénin : le coup d’état qui dit tout haut ce que la région murmure, Revue Conflits, consulté le 22 décembre 2025, https://www.revueconflits.com/benin-le-coup-detat-qui-dit-tout-haut-ce-que-la-region-murmure/