Islamic Jurisprudence Exchanges as Process Support for Mediated Solutions

Lakhdar Ghettas Français | عربي

According to the ICRC, out of the 450 armed groups identified as being of humanitarian concern in 2023, 294 are operating in conflicts in Africa and the Middle East.1 An ICRC briefing has informed that “most armed groups are willing to engage […] but states are the most common obstacle to this engagement [which] runs counter to frequently cited reasons by donors, states, or other humanitarian organizations, as a reason why they do not fund, facilitate, or even attempt engagement with armed groups.”2 More than half of all armed conflicts now involve armed groups that express their interests and claims in explicitly Islamic terms3. A significant number of these conflicts involve jihadi armed groups claiming a religious legitimacy based on Islamic references, as set by the religious scholars of each group.

Major political events in 2022 and 2023 have pushed the Sahel region into an unprecedented humanitarian situation. According to OCHA’s Humanitarian Overview of March 2024, there are 35.2 million vulnerable people in the region, including women, children, and men, in need of humanitarian assistance in Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger. Additionally, the region is home to 5.6 million internally displaced persons and 1.7 million refugees4. This means that one in five people in the Central Sahel is in need of assistance5. Across the Central Sahel, deaths from political violence have increased by 38%, and civilian deaths by more than 18%6. With the escalation of violence in many conflicts, particularly in the West African regions, there have been calls from communities and attempts by governments, for example in Djibo, Burkina Faso, to explore mediated solutions aimed at reducing the hardship and duress faced by civilian communities in the territories wholly or partially under the control of the armed groups7.

Given the limited results of the military campaigns in terms of conflict resolution, voices in the communities affected by the violence, as well as former officials have called for a change of course and the consideration of dialogues that could lead to the lifting of sieges or the sparing of non-combatant civilians in the ongoing conflicts8.

Speaking at the University of Geneva last month, Smail Chergui, the former African Union Commissioner for Peace and Security, noted the failure of previous approaches to stabilising the region. Despite numerous international and local efforts, these strategies have lacked coordination and coherence, leading to almost zero results. In response, Chergui proposes a global approach that guarantees human security and the dignity of the population. In particular, he emphasised the need to involve local leaders and authorities in the development and implementation of policies, as their knowledge of local realities is crucial for effective stabilisation9.

Peace actors have been working with Track II community and religious leaders to break the deadlock and explore local mediated solutions to sieges, school closures, and humanitarian access. Many of these engagement efforts have yielded tangible results in terms of lifting sieges, allowing humanitarian aid to flow, or reopening schools in the Sahel. This engagement with the religious scholars of armed groups with an Islamic reference and worldview takes the form of exchanges on the fundamentals of Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh). They explore the various options offered by Islamic jurisprudence for improving the situation in different conflict contexts with a view to issues such as the rules of conduct of hostilities, local governance, and, ultimately, the conditions for negotiations and sustainable mediated solutions. The effort is a kind of process support for mediation, similar to that undertaken when engaging the political or military leaders of armed groups with a secular worldview. In these fiqhi exchanges, the engagement and exchange take place among scholars of fiqh.

Such a process supports mediation and peacebuilding efforts by raising the awareness of armed groups for various options arising from Islamic jurisprudence for their policies and actions. Examples of these include responsibility for the welfare of populations under insurgent control (food provision, education, health services), the Islamic law of war, and attitudes towards ethnic or religious minorities, and lessons learned from the Islamic tradition (e.g. Sulh al Hudhaybia) for the terms of cease-fires, truces, and peace agreements. The multiplication of options resulting from these exchanges increases flexibility in negotiations and prevents the hardening of positions. More options and an awareness of differences between conflict contexts create more space for sustainable solutions.

Facilitating fiqhi conversations between credible and influential Muslim scholars and members of (or scholars close to) the Consultative (Shura) and Legal (Sharia) bodies of the religiously inspired armed groups, on practical issues related to governance for example, will enable a genuine process of reinterpretation and change in the attitudes and behaviour of these groups towards non-extremism and non-violence and towards governance that respects the whole population which is under their control, and a willingness to dialogue whenever possible.

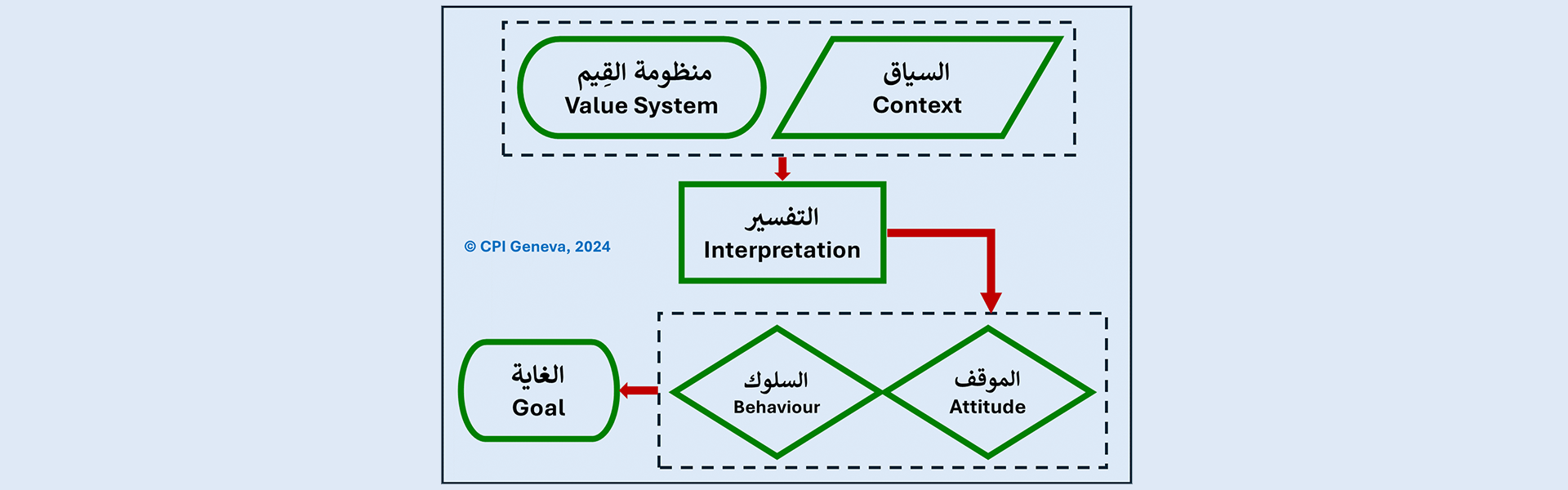

The work of facilitation acts on the dimension of context, helping to understand and read it. In fact, in a mediation support process, mediators often help the parties to better understand the context (international, local) so that they can make better informed decisions. Facilitation also helps with the interpretation by providing resources for additional interpretation options, such as experiences from elsewhere and a historical perspective. It can also suggest options for action in a given situation, in order to help guide or direct action in a way that is compatible with fiqh, wasatiya and dialogue.

Religiously inspired armed groups operate in accordance with a reference (value system) that determines their attitude and behaviour towards others. They also operate within a specific context, and the intertwining of the reference and the context triggers a process of interpretation as to how the reference can be practically used to achieve the desired goal10. The process of interpretation (a re-reading of the value system that does not itself change) is called ijtihad in the Islamic tradition. It produces a legal framework that conditions the practices and actions of the religiously inspired armed groups. In fact, Imam Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyya (1292-1350) defines the origin, the way, and the goal11.Obviously, starting from the same origin (reference), there are different ways (possibilities of interpretation) to reach the same desired goal. The way, subject to interpretation, must serve the goal and be in accordance with the reference. If the way is armed action, it must comply with the religious law of war (with many commonalities to IHL). The compliance to the reference norm is called wasatiya (a median approach), the opposite of ghuluw (extremism)12.

The process of interpretation/ijtihad is not open to everyone; it requires legitimacy and expertise. It is the role and duty of recognized and credible Islamic scholars. (Re)interpretation can be the result of genuine internal deliberations among scholars within or close to activist groups. It can also be assisted by a third party, who must be knowledgeable about the reference and the context, and be perceived by the actors as honest, fair and impartial.

CPI has been undertaking such efforts with its local partners to explore “Fiqhi Pathways”. This process support effort promotes awareness among international policymakers of dialogues and problem-solving initiatives based on Islamic jurisprudence that are already underway. Rooted in a different worldview, it is sometimes a challenge for policymakers – or some conflict parties facing Islamist insurgencies – to understand the “language” the insurgents speak, and what they firmly believe. Fiqhi Pathways proposes to bridge this gap for the sake of conflict transformation.

Lakhdar Ghettas

June 2024

- Matthew Bamber-Zryd. ICRC engagement with armed groups in 2023. ICRC, Geneva, 10 October 2023. ↩︎

- [ICRC Webinar, Global Mapping of Armed Groups, 6 December 2023. ↩︎

- Isak Svensson & Desirée Nilsson. Islamist armed conflicts: A new challenge for conflict resolution? Department of Peace and Conflict Research, Uppsala University, FBA Research-Policy Dialogue on Resolving Islamist Armed Conflicts, October 2021, Stockholm. ↩︎

- OCHA. Sahel Dashboard: Humanitarian Overview. 13 March 2024. ↩︎

- IOM. One in Five People in the Central Sahel Needs Humanitarian Aid: Now is the Time to Act. 12 January 2024. ↩︎

- ACLED. The Sahel: A Deadly New Era in the Decades-Long Conflict. 17 January 2024. ↩︎

- Sam Mednick. Talking to jihadists: How three community leaders took a bold step in Burkina Faso. ‘We discovered that the jihadists have some moral values.’. The New Humanitarian. 25 May 2022. See also:

Sam Mednick. Burkina Faso to support local talks with jihadists: A Q&A with the minister of reconciliation. ‘Everybody wants peace again.’ The New Humanitarian. 27 April 2022. ↩︎ - A Burkinabè community leader. To end the siege on my Burkinabè town, we must open a dialogue with the jihadists. ‘We cannot farm, we cannot raise our livestock, and we cannot trade.’ The New Humanitarian. 8 February 2024. ↩︎

- Smail Chergui, Les nouveaux enjeux de paix et de sécurité dans l’espace Méditerranéen : le cas du Sahel. Public conference. University of Geneva, 2 May 2024. ↩︎

- Abbas Aroua, Jean-Nicolas Bitter, Simon J. A. Mason. The Role of Value Systems in Conflict Resolution. Policy Perspectives. Vol. 9/9. CSS/ETH Zurich. November 2021. ↩︎

- Abbas Aroua. The Origin, the Way and the Goal: Imam Ibn Al-Qayyim’s Typology of Conflict. Cordoba Research Papers. Cordoba Peace Institute – Geneva. June 2023. ↩︎

- Abbas Aroua. Addressing Extremism and Violence: The Importance of Terminology. Cordoba Research Papers. Cordoba Peace Institute – Geneva. January 2018. ↩︎