Violence and tyranny are not the destiny of Muslim peoples

I have recently been a guest of the Cordoba Peace Institute – Geneva (CPI), a Swiss organization that has celebrated its 20th anniversary in the past few days. What this organization has done throughout its relatively short career goes beyond its size and human and financial capacities. The institute’s strategic goal is to “prevent violence, transform conflicts and promote peace”.

By Salaheddine Jourchi, Member of the Consultative Committee of CPI

By Salaheddine Jourchi, Member of the Consultative Committee of CPI

I have recently been a guest of the Cordoba Peace Institute – Geneva (CPI), a Swiss organization that has celebrated its 20th anniversary in the past few days. What this organization has done throughout its relatively short career goes beyond its size and human and financial capacities. The institute’s strategic goal is to “prevent violence, transform conflicts and promote peace”.

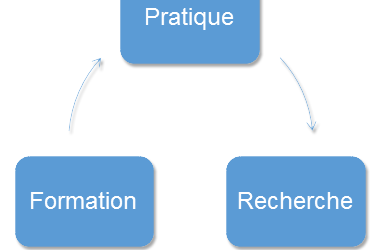

For an association or entity to address the challenges and obstacles to peace in a sensitive region such as the Arab-Muslim world is not an easy task, especially since many of the conflicts that erupt from time to time are complex in nature in which the political intertwines with the religious, tribal, and economic, requiring a high degree of foresight, wisdom, awareness, and patience. CPI has successfully dealt with many issues that have occupied the governments, elites, and peoples of the region, relying on the mechanisms of dialogue, good listening and broadening the common and shared base. Contrary to what many people believe, a shared base exists between people, regardless of their differences, and this base is capable of being developed and expanded, provided that the will is there, and the protagonists renounce the intolerance that destroys the values of living together.

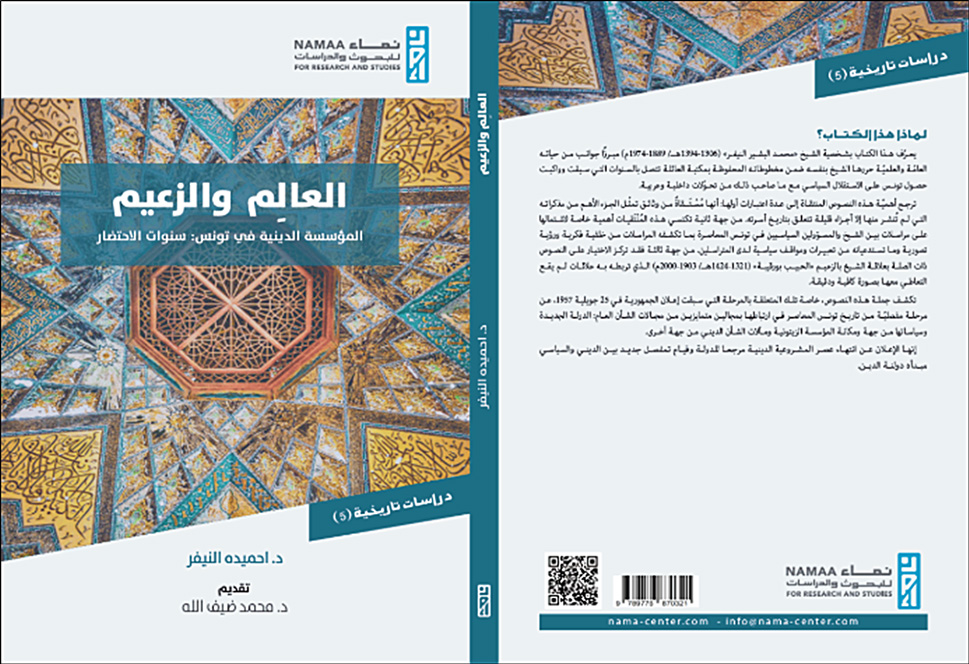

On this occasion, the Tunisian academic, Hmida Ennaifer, was invited to present his new book, entitled “The Scholar and the Leader”. This book deals with the content of letters exchanged between the author’s grandfather, Sheikh Ennaifer, and President Habib Bourguiba, during the establishment of the nation state, a dialogue that took place between two contradictory mentalities in terms of both vision and method. On the one hand, a scholar of the University Ez-Zitouna who wanted to understand the reasons that pushed Bourguiba to choose radical treatment to change a situation that was collapsing, such as abolishing the teaching of Ez-Zitouna, to rely entirely on a modern education taking the French system as a model to follow, and on the other, a leader anxious to exploit the historical context to undertake a number of reforms that had lived in his imagination since he was a student at the Sorbonne. The dialogue between the two men was not successful, nor was the attempt to reach a historic settlement that some still believe possible to this day.

CPI’s interest in the relationship between the religious and the political stems from its leaders’ awareness that this issue still represents one of the lines of conflict and division in the Middle East. That is why the Institute has set as one of its objectives “to address polarizations and tensions between Muslim actors of various religious references in the local contexts of Middle Eastern countries,” also working to reduce violent extremism among young Muslims by “raising awareness of the Islamic discourse of the middle way”.

In this context, a diverse program had been implemented, involving many actors from various regions, including sub-Saharan African countries. The Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs has supported this ambitious program through its “Religion, Politics and Conflict” sector of activity.

CPI’s interest in Tunisia is not new, as it had previously worked to accompany the democratic transition and had set up a program in coordination with the “Al-Jahidh Forum” that sought to assess the Tunisian experience in terms of possible relations between elite components belonging to the main currents: Islamists on the one hand and secularists on the other. CPI also cooperated with the “Tunisian League for Culture and Pluralism”.

Attention focused on Tunisia after the Troika experience and the rise to power of the Nidaa Tounes party. It seems that the dialogue that took place between politicians and intellectuals close to the political scene, some of whom had assumed responsibilities in previous governments, had relatively reassured CPI officials about the future of the Tunisian experience, believing that this experience was irreversible. It is true that they noticed that the distance between the two parties was still wide and fraught with difficulties, especially between the Ennahda movement and the radical left as a whole, but they expected that progress on the democratic path would dissolve the differences and mature the two parties, and they believed that the political transition had become guaranteed. They did not expect that the cards would be reshuffled, that the direction of the wind would change, that a new equation would emerge, and that autocracy would return with surprising speed, so that Tunisia would once again find itself in the battle for the defense of freedoms, and that political, cultural, and social organizations would return to bipolarization and ideological rivalry for power, to the detriment of Tunisia and the interests of its people.

The main challenge in Tunisia and in the countries of the region will remain to provide guarantees to “advance dialogue and enable people to prevent violence and transform conflicts in societies where Muslims live”. This does not mean that Muslims are necessarily an obstacle to coexistence, because there are followers of other religions who behave with violence and reject the right to difference, but this does not diminish the danger of ideas and policies that could threaten stability and coexistence and position religion against freedom.

There are concepts that have the effect of justifying exclusion and religious and social segregation in many countries and contexts, which have so far shaken democracy in Arab and Muslim societies, prompting some to emphasize the inevitable “Islamic intransigence”. This is an insufficient approach to explain the phenomenon of tyranny, although experiences here and there support this hypothesis, and push its proponents to try to make it an “historical determinism”; their last argument being what is happening in Tunisia, which they describe as the final failed attempt to bet on liberation from tyranny. But the peoples will prove otherwise and confirm that Muslims’ path to democracy is a possible choice.

(Arabi 21, 7 November 2022)